How to Balance Breadth and Depth in Your Career

In this article, I explore the ideas that help us balance breadth and depth in our careers for maximum impact. 3 interconnected areas. 3 questions in each. 1 lifetime of experiments.

Are You a Hedgehog or a Fox?

The metaphor of the Hedgehog and the Fox comes from the eponymous essay by Isaiah Berlin:

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing... Taken figuratively, the words can be made to yield a sense in which they mark one of the deepest differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general. For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel - a single, universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance - and on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related by no moral or aesthetic principle.

It is likely that in your career you have faced - and maybe more than on one occasion, - a tradeoff between breadth and depth. The tradeoff exists largely because our career time is limited. Each of us has only 24 hours a day and only that many career years. We need time to explore: acquire skills, knowledge, build career capital and figure out where we are at our best. We also need time to exploit our skills, knowledge and career capital to make an impact. Prof. Alvarez broadly summarized career differences between career "hedgehogs" and "foxes" as follows:

Source: INSEAD Webinar “Executive Careers in the Face of Change”, by Prof. Alvarez

I took these definitions as my starting point and went on to explore the ideas and principles that can guide us HOW and WHEN to choose breadth in favor of depth and vice versa. I was looking for these ideas and principles in three key elements that dynamically interact and contribute to success, be it business/entrepreneurial success, or career success:

· Environment (E)

· Ourselves (O)

· Strategy (S)

I owe this "E-O-S" trinity (NB: in the original framework "O" stands for Organisation) to the INSEAD Professor, Joe Santos, whose courses "Managing Enterprise Performance" and "Managing Multinational Enterprise Performance" have greatly impacted my thinking about general management and career.

Part One. E - ENVIRONMENT

We ask ourselves 3 questions.

How kind/wicked is the environment I am evolving / interested in?

Psychologist Robin Hogarth distinguished between two different kinds of domains/learning environments.

Kind learning environments are relatively stable and predictable ones, where patterns repeat and feedback is quick and accurate. Problems are known and well defined, and we optimize for efficiency and therefore DEPTH is welcome. Examples: relatively stable established operations or supply chains, sport, music, classical dance, medicine/surgery, airlines & hospitality (until COVID-19).

Wicked environments (or VUCA environments, combining volatility/uncertainty/complexity/ambiguity) are unstable, with incomplete or unclear rules of the game and delayed or inaccurate feedback. In such environments, we need BREADTH to adapt, because tried and tested recipes may not work.

In general, business environments in which we build our careers become more and more wicked, more VUCA - and the pandemic is the best illustration thereof. We need more BREADTH that drives adaptability and creativity.

2. How future-proof is my domain/job?

In his graduation speech that he never actually delivered, "What You'll Wish You'd Known" Paul Graham says:

Most of the work I've done in the last ten years didn't exist when I was in high school. The world changes fast, and the rate at which it changes is itself speeding up. In such a world it's not a good idea to have fixed plans.

Don't fall a Victim of Automation

How big is the opportunity your current job/industry offers? How high are the chances that the job I am doing will become obsolete? In their 2013 study "The Future of Employment", Frey and Osborne examined how susceptible jobs are to automation. According to their estimates, about 47% of the US employment is at risk, and that wages and educational attainment exhibit a strong negative relationship with an occupation's probability of computerization. The table at the end of the study contains the list of 702 occupations, ranked from the least to the most prone to automation. The more prone your job is to automation, the more BREADTH you would need to remain relevant - ideally in skills and occupations that are less susceptible to be wiped out by automation.

Work on Hard Problems

As far as the domains/industries are concerned, the brilliant "Guide to using your career to help solve the world's most pressing problems" by Benjamin Todd and the 80,000 Hours team offers important thoughts on the global priorities and the most pressing problems to work on. I like the way they suggest thinking about the career options that make a difference most effectively:

The issues where additional resources will have the greatest returns are those that have the best overall combination of being (i)important to the long-term future, (ii) neglected relative to their importance, and (iii) unusually tractable."

The better the combination you are involved in or considering, the more long-term game you are going to play and the higher are chances that DEPTH will make an impact.

Look for Leverage

Another, very interesting view on the impact you can achieve, comes from the must-read "How to Get Rich" series by Naval Ravikant.

You want a career where your inputs don't match your outputs. Businesses that have high creativity and high leverage tend to be the ones where you could do an hour of work, and it can have a huge effect, or you can do 1,000 hours of work, and it can have no effect. One great software engineer can for example create bitcoin, and create billions of dollars' worth of value… Whereas on the extreme end, if you're a lumberjack, even the best lumberjack in the world may be just 3x better than one of the worst lumberjacks. It’s not gonna be a gigantic difference. So, you want to look for professions or careers where the inputs and outputs are highly disconnected. This is another way of saying than you want to look for things that are leveraged… The higher creativity component of a profession, the more likely it is to have disconnected inputs and outputs". Leverage needs creativity. And creativity needs BREADTH - this breadth first and foremost implies the breadth of knowledge and ideas, not necessarily breadths of roles and skills.

3. How can I improve my odds of success?

Whether we want to admit it or not, there is a large element of luck that determines our career paths. However, not all luck is the same. I like the definition of the four kinds of luck that originally comes from the book "Chase, Chance, and Creativity" by James Austin, and the interpretation thereof I have also found in the "How to Get Rich" series by Naval Ravikant. Depth and breadth attract different kinds of luck.

The Four Kinds of Luck

· Blind luck. I got lucky because something out of my control happened. That's pure fortune and has no relationship whatsoever to depth or breadth.

· Luck from hustling. This luck comes through persistence, hard work, hustle, motion. It's testing a lot of things and seeing what works. This luck comes from BREADTH.

· Luck from preparation. This luck has more chances to happen when you are good at spotting it - if you are skilled in the field, you will notice when a lucky break happens in that field, while others, less attuned, will not notice. This luck comes through skill and knowledge, through DEPTH.

· Luck from your unique character. This luck comes from the unique character that you build, your unique brand, and your mindset. Building your unique brand usually requires first BREADTH, a sampling period, and then DEPTH, and we will talk more about it in the next section.

Good + Good > Excellent

Another interesting take on luck comes from Scott Adams. I would call it selective breadth. In his book "How to Fail at Almost Everything And Still Win Big", he argues that the world is math, not magic, defines the success formula as "Good + Good > Excellent" and suggests that

You can't directly control luck, but you can move from a game with low odds of success to a game with better odds… The future is thoroughly unpredictable when it comes to your profession and your personal life ten years out. The best way to increase your odds of success - in a way that might look like luck to others - is to systematically become good, but not amazing, at the types of skills that work well together and are highly useful for just about any job.

Whatever the specific technical domain, knowledge, or skills you might fall in love with and that will build your unique character (further on that in the next section), going selectively broad to acquire the foundational transversal skills will increase your chances of career success. Here is my list, inspired by the two gentlemen I've just quoted, with my own twist:

· Ultimate foundations of critical & clear thinking: mathematics and logic. Naval Ravikant: "If you understand logic and mathematics, then you have the basis for understanding the scientific method. Once you understand the scientific method, then you can understand how to separate truth from falsehood in other fields and other things that you're reading." Combined with philosophy and system thinking, critical thinking lays a good foundation for better decision-making.

· Learning how to learn. Learning is a skill in itself. Reading is one big component of learning. Doing, Practicing is another. You can have an edge in many skills if you can learn faster and stickier than other people. "Ultralearning" by Scott Young is a great resource to upgrade your learning techniques.

· "Selling", or all the skills that increase the impact of your communication: writing, storytelling & storytelling with numbers, presentation, public speaking, proper voice technique, psychology of persuasion, foreign languages.

· Arts & Design: it could be an icing on the cake, but I believe that the beauty and harmony we can find in pursuing one or many artistic endeavors can be an endless source of creativity in all other endeavors.

Part Two. O - OURSELVES

Here again, we ask ourselves 3 questions.

How far is what I am doing from what I think I want?

We can answer this question in three steps, guided by the brilliant essay "How to Pick a Career (That Actually Fits You)" by Tim Urban.

Step One. The Want Box and the Yearning Octopus

We start with the Want Box & the Yearning Octopus with five tentacles - Personal, Social, Lifestyle, Moral, Practical. I really like this framework that helps us think about our Wants and probe the extent to which these wants are our own and not someone else's.

Source: waitbutwhy.com

Step Two. The Yearning Hierarchy

We use the Yearning Hierarchy to arrange our yearnings on different shelves by order of importance.

Source: waitbutwhy.com

Another frame to think about our wants is motivation theory by Frederick Herzberg. Clayton Christensen outlines it in his book "How Will You Measure Your Life?"

There are the elements of work that, if not done right, will cause us to be dissatisfied. These are called hygiene factors. Hygiene factors are things like status, compensation, job security, work conditions, company policies. Bad hygiene factors cause dissatisfaction. The things that truly, deeply satisfy us are motivators. They may include challenging work, recognition, responsibility, personal growth. Motivation is much less about external prodding or stimulation, and much more about what's inside of you, and inside of your work.

What are your hygiene factors? What are your motivators?

Step Three. Gap Analysis

We compare our Yearning Box with the actual things we are doing - the wider the gap, the further what we do is from our motivators, the more BREADTH we need - to go and explore something else.

The Want Box Needs a Reality Check

I've intentionally put a catch into the question - our Want Box / Yearning Hierarchy contains what we THINK we want. Quite often, especially at a younger age, we have no idea what we really want. Sometimes, it's easier to define what we DON'T WANT. Our wants will not all stay the same throughout our entire life. Also, we do not live in a vacuum, and if we are married / in a relationship, our Want Box can be in harmony or in a clash with that of our partner. Whatever the case, our want box needs a reality check. We need to actually try things to find out if their impact is what we want.

Long story short, the less certain we are about what we want, the more is the need for BREADTH and experimenting further. Learning about stuff also means learning about ourselves.

2. How in love am I with what I'm doing?

Here I suggest thinking about it, not as a job or career path as a whole but breaking it down to specific knowledge, skills, or situations we really love. Usually, things we are good at happen to be the same things that we love. I, for example, love solving problems where I can use both my left, analytical brain and my creative and compassionate right brain. I love the areas where domains overlap: for example, technology and how people use it. Or, let's imagine you are a skillful negotiator, then it might not matter what is the subject of the negotiation, you love negotiating about anything. If you like turning businesses around, then, the exact nature of business might be secondary to the excitement and pride of being able to bring a positive change.

The cause-and-effect relationship between being good at something and loving it, if there is any, can go both ways: we are good at it because we love it, or we come to love it when we become good at it. This means that sometimes we need to give ourselves time to become good at something in order to understand whether we love it or not.

Some studies use the term "match quality" or "personal fit". I call it "love". It's like the love we can feel towards someone: it can happen at any age, it can strike us at first sight, or grow slowly. It's hard to define, but when it's there, we know it.

Expected Impact = Average Impact of the Role x Personal Fit

To quote 80,000 Hours,

personal fit is likely one of the most important things in determining the expected impact of your career.

The more love we feel towards something, the DEEPER we would want to go because we will be able to truly excel only in the things we love. They will shape our unique character. They will make us interesting. They will help us create a unique life story. Eccentricities & Obsessions are welcome here too. Just a joke of caution from David Ogilvy:

Develop your eccentricities while you're young. That way, when you get old, people won't think you're going gaga.

No one can compete with you on being you

Things we really love will attract the fourth kind of luck, even if they are the weirdest, the most obscure, or eccentric things on Earth, because, to quote "How to Get Rich" again,

The more authentic you are to who you are, and what you love to do, the less competition you're gonna have. So, you can escape competition through authenticity when you realize that no one can compete with you on being you… The internet has massively broadened career possibilities. It allows you to scale any niche obsession. You can go out on the internet, and you can find your audience. And you can build a business, and create a product, and build wealth, and make people happy just uniquely expressing yourself through the internet.

Polymaths Win

The real magic happens when our depth in certain specific skills or domains comes in combination with breadth in foundational skills & knowledge. This is close to the "polymath" definition from "Range": persons with broad skills or interests and with at least one area of depth. Polymaths tend to be the best innovators and inventors.

3. To what extent do the things I am good at hinder my learning and growth?

We often come to see the things we know and love doing as part of our identity, as being authentic. But how capable are we to drop our familiar and favorite tools in the face of a changing environment, in the presence of "what got you here won't get you there" situations?

The Authenticity Paradox

The way we stick to the familiar and loved tools combined with the way we think about authenticity can hinder our learning and growth. Herminia Ibarra from London Business School calls it "the Authenticity Paradox", and I heartily recommend both her TED talk on the topic as well as her book "Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader". When we face a tradeoff between what it takes to be effective and "being ourselves", we often stick to the most conservative and cautious version of ourselves, the one based on the "things that got us here", because we can morally justify it as "being authentic", even if it is completely ineffective. It's not easy to draw the line between authenticity and rigidity.

Whenever we face "what got you here won't get you there" situations, we need more BREADTH & experimentation, we need to be more "foxy", less rigid, even if we can initially feel uncomfortable and, let's face it, completely inauthentic. We cannot THINK our way out of the Authenticity Paradox, we can only ACT our way into a new way of thinking about ourselves. We can be more playful with our possible selves and see authenticity as continuous 'self-authoring.

Part Three. S - STRATEGY

Now it's time to ask the 3 final questions.

1. How do I choose my next career goals?

The surprising answer to this question is that it may be a better idea if you don't choose any. Instead of defining and pursuing "big hairy audacious" career goals we can be better off focusing on building good systems.

Goals are for Losers

For the first time I stumbled upon the idea of growth without goals on the Investor Field Guide website by Patrick O'Shaughnessy:

The key isn’t thinking long-term, which implies long-term goals. Long-term thinking is really just goalless thinking. Long-term “success” probably just comes from an emphasis on process and mindset in the present. Long term thinking is also made possible by denying its opposite: short-term thinking."

Process and mindset are a system. James Clear in "Atomic Habits" asks an interesting question: "If you completely ignored your goals and focused only on your system, would you still succeed?" and goes on to identify the problems that arise when we focus too much on the goals and not on designing and building a good system:

· Winners and losers have the same goals. There is a big survivorship bias in how we think about the winners, mistakenly assuming that ambitious goals led to their success, while overlooking both the losers and the systems the winners have built to succeed.

· Achieving a goal only changes our life for the moment.

· Goals restrict our happiness: we are continually putting happiness off until the next milestone. "A system-first mentality provides the antidote. When you fall in love with the process rather than the product, you don't have to wait to give yourself permission to be happy. You can be satisfied every time your system is running."

· Goals are at odds with long-term processes. "The purpose of setting goals is to win the game. The purpose of building systems is to continue playing the game. True long-term thinking is goal-less thinking… It's about the cycle of endless refinement and continuous improvement. Ultimately, it's your commitment to the process that will determine your progress".

Both authors found inspiration in the ideas of Scott Adams who talked about advantages of systems over goals in "How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big":

Goals are for losers… Goal-oriented people exist in a state of nearly continuous failure that they hope will be temporary. That feeling wears on you. In time, it becomes heavy and uncomfortable. It might even drive you out of the game… In most cases, as far as I can tell, the people who use systems do better.

Work Forward from Promising Situations

Rosamund Stone Zander and Benjamin Zander in "The Art of Possibility" propose a practice that helps shift the focus from goals and measurement to systems and possibility - the practice of "Giving an A":

Michelangelo is often quoted as having said that inside every block of marble dwells a beautiful statue; one need only remove the excess material to reveal the work of art within… We call this practice giving an A. The practice of giving an A transforms (…) the world of measurement into the universe of possibility. This A can be given to anyone in any walk of life. This A is not an expectation to live up to, but a possibility to live into.

So what do we do if we don't set any goals? Paul Graham suggests:

Instead of working back from a goal, work forward from promising situations. This is what most successful people actually do anyway. In the graduation-speech approach, you decide where you want to be in twenty years, and then ask: what should I do now to get there? I propose instead that you don't commit to anything in the future, but just look at the options available now, and choose those that will give you the most promising range of options afterward. It's not so important what you work on, so long as you're not wasting your time. Work on things that interest you and increase your options, and worry later about which you'll take.

2. What is a good system to explore my options?

Action Beats Motion

The first key idea for a good exploratory system is the distinction between being in motion and taking action. I stumbled upon this distinction in James Clear's book "Atomic Habits" and found it super important:

The two ideas sound similar, but they're not the same. When you're in motion, you're planning and strategizing and learning. Those are all good things, but they don't produce a result. Action, on the other hand, is the type of behavior that will deliver an outcome. If I outline twenty ideas for articles I want to write, that's motion. If I actually sit down and write an article, that's action… If motion doesn't lead to results, why do we do it? Sometimes we do it because we actually need to plan or learn more. However, more often than not, we do it because motion allows us to feel like we're making progress without running a risk of failure… Motion makes you feel like you're getting things done. But really, you're just preparing to get something done. When preparation becomes a form of procrastination, you need to change something. You don't want to merely be planning. You want to be practicing.

Bias for action is really the key idea for any exploratory tests we will undertake. In exploration, action beats motion. Testing beats analysis paralysis. Practice beats learning. In designing our experiments, we should always privilege those with more practice and action, because the information value we will get from those experiments will be higher.

A Ladder of Tests

Every exploratory move comes at a cost: time, money, opportunity cost. It can be a good idea to start exploring the low-cost experiments before deciding if we want to be more engaged.

I like the idea of a ladder of tests, proposed by 80,000 Hours team:

When investigating your options, we find it useful to think of a ladder of tests that go in ascending order of cost, and aim to settle the key uncertainties you’ve identified. We often encounter people considering taking drastic action – like quitting their job – before taking lower cost ways to learn more about what’s best first.

Let's say we want to explore a career transition into another industry sector. The ladder of tests could look as follows:

A. Do desktop research and read articles about the area you want to break into (1-2 hours)

B. Talk to one person working in this field (2 hours in total to find the person, fix the time for a talk, prepare for it, and have 30 mins conversation)

C. Speak to three more people working in the area, read 1-2 books, with the aim to gain the key ideas, vocabulary and to understand the most effective ways to enter the area given your background (20h)

D. 1-4 weeks' project: applying for lots of jobs, getting involved in a side project at work, volunteering in a related role, starting a blog, etc. Previous lower-cost steps should have helped define this project.

E. 2-24 months' commitment. Sometimes it's very tempting, especially if we feel really frustrated with a status quo, to do a big jump straight into the big but unknown commitment. It can play out, but it can also fail spectacularly. Big commitment is harder or even impossible to reverse. All else equal, the higher the stakes of the decision, the more time we should spend investigating.

Exploring while in a dual-career couple

Things get really interesting when we find ourselves in a dual-career couple, with both partners periodically in strong need to explore their next career moves. On one hand, there are more constraints, because it's not one but two careers, and kids, etc. On the other hand, being in a couple can be a source of extra flexibility. The reality and opportunities can be very different for many couples. My rule of thumb is that it's better to do high-cost experiments asynchronously: when one partner goes exploring in a high uncertainty environment, the other can remain a secure base and vice versa. To solve dual-career equations in your couple, I strongly recommend Jennifer Petriglieri's book "Couples That Work": she identifies three key phases of exploration and personal growth in every couple's work-life journey and proposes ideas that help navigate these periods together and strengthen their bond.

3. When to explore and when to commit?

The timing to switch from breadth to depth, from search to commitment is a big question. The underlying nature of this question varies depending on the stage of our careers. Inspired by the ideas in Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths's book "Algorithms to Live By: the Computer Science of Human Decisions", I like to think about it as two distinct problems:

· In the beginning of our career, it’s more about learning about ourselves and finding our favorites. It's essentially the Optimal Stopping, which tells us when to look and when to leap.

· Once we have moved to mid-career, we have usually found our favorites and built a certain career capital. The move between depth and breadth essentially becomes Explore/Exploit Tradeoff that helps us find the balance between trying new things and enjoying our favorites.

There are a few ideas and theories that help solve both problems.

Earlier Career: Optimal Stopping Problem

I like this thought from "Range":

If we treated careers more like dating, nobody would settle down so quickly.

However, unlike in dating, in careers, we tend to commit too early. Computer scientists call it premature optimization.

In the beginning of our careers, like in dating, we need to explore. We need a sampling period. Learning and practicing different things help us learn about ourselves. Geniuses who found their passion early and stuck with it do exist, and they make great stories, but they are notable exceptions, not the rule. Most of us early in our careers have little idea what we want to do and what we can be good at. Back to Paul Graham:

In the graduation-speech approach, you decide where you want to be in twenty years, and then ask: what should I do now to get there? I propose instead that you don't commit to anything in the future, but just look at the options available now, and choose those that will give you the most promising range of options afterward. It's not so important what you work on, so long as you're not wasting your time. Work on things that interest you and increase your options, and worry later about which you'll take.

We need to go as broad as possible, but we don't want the initial search to last forever. To quote "Algorithms to Live By":

In any optimal stopping problem, the crucial dilemma is not which option to pick, but how many options to even consider.

One solution to the Optimal Stopping problem can be Look-Then-Leap rule:

You set a pre-determined amount of time for "looking" - that is, exploring your options, gathering data - in which you categorically don't choose anyone, no matter how impressive. After that point, you enter the "leap" phase, prepared to instantly commit to anyone who outshines the best applicant you saw in the look phase.

Translated to career situations, we set ourselves certain times to try out different career options, domains, and roles and don’t commit until this period is over. The key during this period is to (1) explore as many options as possible and (2) have as much impact as possible while exploring.

To explore as many options as possible within a limited time, we need career opportunities with the most learning upside. Some options are better than others. In big companies, graduate programs offer good rotation and exposure to different areas of the company, within 2-3 years. Working in smaller companies or startups can be a great option too, because structures are lean and resources scarce, so there we can get exposure and practice in many different areas. Even if you join a large company for a narrow function, it's entirely up to you to go and explore by talking to people, offering help in transversal projects etc. It’s a mix of external opportunities and the explorer attitude we take.

The impact is crucial for building the initial career capital. You might not have specific skills and knowledge yet, however, the better you are in the foundational transversal skills we discussed earlier, the more impact you will be able to achieve.

Mid- to Late Career: Explore/Exploit Tradeoff

I like the story from Scott Adam's "How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big": on a plane to California where he was going to look for his first job, he sat next to a gentleman in his sixties who happened to be a CEO. This businessman gave Adams some career advice. He said that as soon as he got a job, he immediately started looking for a better one. Job seeking was not something one did when necessary, it was an ongoing process. Your job is not your job. Your job is to find a better job = a system instead of a goal; the system to continually look for better options.

By mid-career, we have usually built a certain career capital, and even if the changes in the external environment or in ourselves suggest we would be better off exploring, we stick to our old favorites, instead of looking for better options. Computer scientists call it explore/exploit tradeoff: "exploration is gathering information, and exploitation is using the information you have to get a known good result." Brian Christian goes on and suggests that

when balancing favorite experiences and new ones, nothing matters as much as the interval over which we plan to enjoy them.

The value of exploration can only go down over time, while the value of exploitation can only go up. The interval makes the strategy.

Does it mean that the later we are in our career, the less exploratory should we become? In theory yes, but the answer is not that straightforward.

Computer science offers a few strategies for solving explore/exploit tradeoff.

One is Win-Stay, Lose-Shift: keep exploiting as long as the option is paying off, whatever is your definition of the payoff. If it happens that an option stopped paying off late in your career, you have nothing to do but to reinvent yourself.

Another solution is the Gittins index: always play the option with the highest number that expresses the benefits of exploration and exploitation. This solution formally highlights preference for the unknown, provided we have some opportunity to exploit the results of what we learn from exploring. In other words, the Gittins index approach suggests to us that taking the future into account, we should never fully stop exploring.

Finally, there is a regret minimization framework. “Algorithms to Live By” offers a quote from Chester Barnard: "To try and fail is at least to learn; to fail to try is to suffer an inestimable loss of what might have been". Following the advice of regret minimization algorithms, we should be "excited to meet new people and try new things - to assume the best about them, in the absence of evidence of the contrary. In the long run, optimism is the best prevention for regret.

If all this has seemed too complicated, there is another good framework.

Emergent vs Deliberate Strategy

The idea of a "dance" between the emergent and deliberate strategies for our careers comes from Clayton Christensen, who got inspired by the ideas of Henry Mintzberg. Christensen writes about it in "How Will You Measure Your Life?"

Options for your strategy come from two very different sources. The first source is anticipated opportunities - the opportunities that you can see and choose to pursue. A plan focused on anticipated opportunities is a deliberate strategy (= exploit). When a mix of challenges and opportunities comes into play, they form an emergent strategy (= explore).

Christensen writes:

In our lives and in our careers, whether we are aware of it or not, we are constantly navigating a path between deciding between our deliberate strategies and the unanticipated alternatives that emerge…If you have found an outlet in your career that provides both the requisite hygiene factors and motivators, then a deliberate approach makes sense… But if you haven't reached the point of finding a career that does this for you, you need to be emergent, experiment in life. As you learn from experiment, adjust. Then iterate quickly… Strategy always emerges from combination of deliberate and unanticipated opportunities. What's important is to get out there and try stuff until you learn where your talents, interests, and priorities begin to pay off. When you find out what really works for you, then it's time to flip from an emergent strategy to a deliberate one.

The dangers of too much breadth and too much depth and the antidote for both

People can form a superficial judgment about your career based on your nominal years of experience in a certain role.

If it's too much of the same, they can label you as rigid and lacking dynamism. A legitimate question: if you say you have twenty years' experience, is it rather that you have one year's experience, repeated twenty times?

If it's too much hopping between roles, they can dub you a "functional tourist". We tend to jump to justify why it was so, we get complicated and defensive.

The best defense between both reproaches is the impact that we made. If we achieved great things, our impact will silence the critics who did not care to look below the surface. Our impact will make others forget the numbers on our CVs. The impact is all that really counts for a good career and life story.

Whether we choose to go broad, or dive deep, we should seek to make an impact.

Part Four. Bringing It All Together.

In our life and careers, there will always be three things that will be in constant motion:

· Environment will change.

· Our skills and preferences will change.

· Strategy will change.

These three elements will always be in an interplay and together, they will gradually form our life and career, unique, and, hopefully, interesting and impactful.

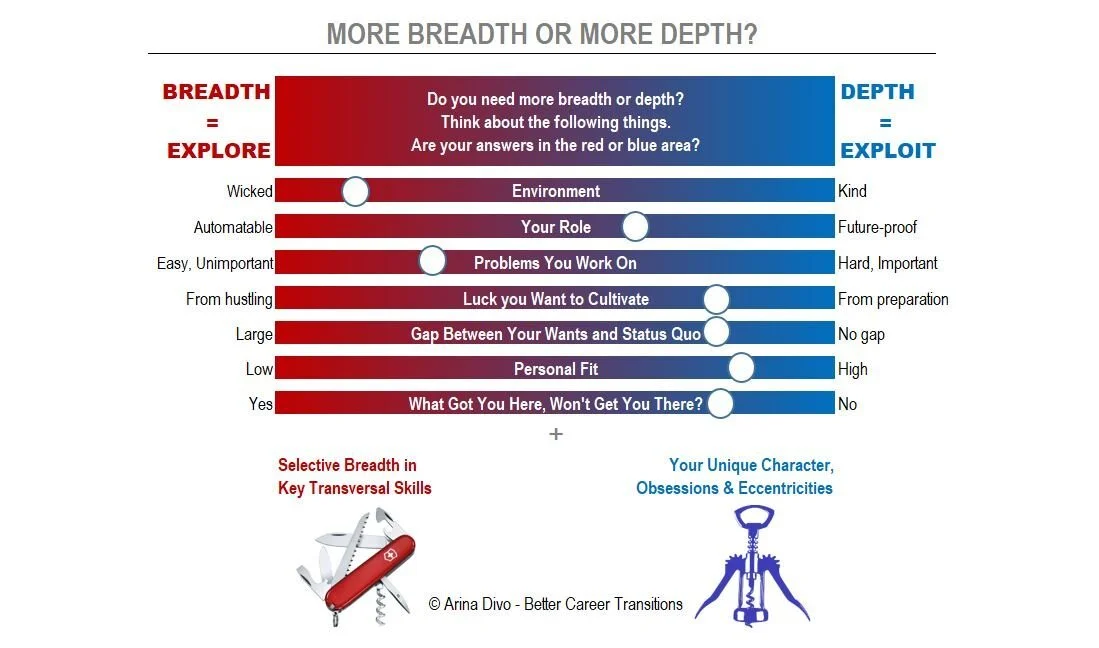

I have summarized the questions to ask ourselves in the following figure, showing my own answers at this stage. Try asking these questions yourself and see where your cursors are. If most of your answers are in the red zone, time is ripe for change and bringing more breadth into your career. Do you feel behind / too old/scared to change? Let me remind you of a proverb: "The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now."

If most of your answers are in the red zone, it sounds like you need more exploration. The exploratory moves don’t always mean changing your job. It makes sense to start with low-cost options.

If most of your answers are in the blue, then it’s a good idea to go even deeper, strive for mastery and make the most impact of your talents.

If it's a mix, your answers will hint you about the areas to look for more breadth: If your personal fit for the role is great, but you feel that you are not making enough impact because the problems you solve are not that important, you might think to change the industry. If you have been a great fit for the role, but now face a ‘What Got You Here, Won’t Get You There’ situation, you might go broader without changing the company, simply by enlarging your skills ‘repertoire’.

And we will always be better and stronger by honing our foundational transversal skills as well as by developing our own, unique obsessions.

Whatever the age and stage of our careers, we should not feel behind. The only person we should compare ourselves to is us, yesterday.

Thank you for reading all the way here. I wish us all an interesting, fulfilling and impactful life and career. I am curious to know about your take on balancing depth and breadth, as well as about the ideas that influenced your views - please get in touch. Thank you.